Music Education in Malaysia: An Overview

By Johami Abdullah

(Specialist Teachers Training College)

This article acquaints American music educators with the general status of music education in Malaysia,' a fast-developing Southeast Asian country. Most of Malaysian music education remains strongly influenced by the colonial legacy of the British, but many changes are occurring as more and more Malaysian music educators trained in America and elsewhere begin to update the formal music education process. Malaysiais a nation involved in finding its own culture and traditions after over 400 years of varying degrees of European influence and domination. Known as Malaya prior to its independence in 1957, this fast-growing country includes in its population a number of distinct ethnic subcultures as well as the majority indigenous Malaysians, and each group traditionally has provided schools at various levels. Yet, although there is a long and rich tradition of education in Malaysia, formal music education in the Malaysian schools is a fairly recent development. Some of the reasons for this may be found in our recent history.

The chief function of education during the British rule was to provide a work force of English-speaking locals to fill sub-managerial and other supervisory posts in both the public and private sectors. Thus, a balanced education with an equal emphasis in the arts and the sciences was not traditionally a concern of the Malaysian schools. Moreover, the Malaysian populace was systematically indoctrinated with the notion that English ideas were second to none in many important spheres of Malaysian life, including education, law, medicine, civil administration, and politics. Such British endeavors have been successful in keeping a sizeable portion of Malaysians tied psychologically to the United Kingdom, although this situation is slowly changing. These older Malaysians, quite understandably, have been apprehensive, wary, and even pejorative of approaches and ideas that are not perceived to be from England. Non-English ideas on music education have also been considered inferior, unsuitable, or without standards. For people who think along these lines, England remains the Mecca of music education. Expectations of music educators have also been influenced by perceptions of British traditions, and music education has seldom been considered a specialized subdiscipline of music study. Many believe that anyone who has acquired some formal qualifications in Western music and can play a standard Western instrument in the classical tradition, is fully qualified as a music educator. Even practicing music educators do not regard as important the knowledge of sub-disciplines such as music psychology, musicology,music therapy, and ethnomusicology.

Formal music education became a compulsory subject in all elementary schools in

Malaysia only in 1983-some 26 years after independence from the British. Much of the

curricular content in these courses is based on the colonial British system of education, or at least patterned along similar ideas. Unfortunately, Malaysian traditional music and the music of other non-European cultures receive non-consequential attention, even in the present curriculum. Music has yet to enter the formal curriculum in Malaysian high schools and universities, where it is treated only as an educational frill. Also, issues in music education like "utilitarian function" and "aesthetic education," which have been debated and discussed in the United States, are unknown in Malaysia.

Overseas Training for Malaysian Music Educators

The Malaysian government, especially under the leadership of our present prime

minister, began in the late 1970s to counter Malaysian over-dependence on Britain. To

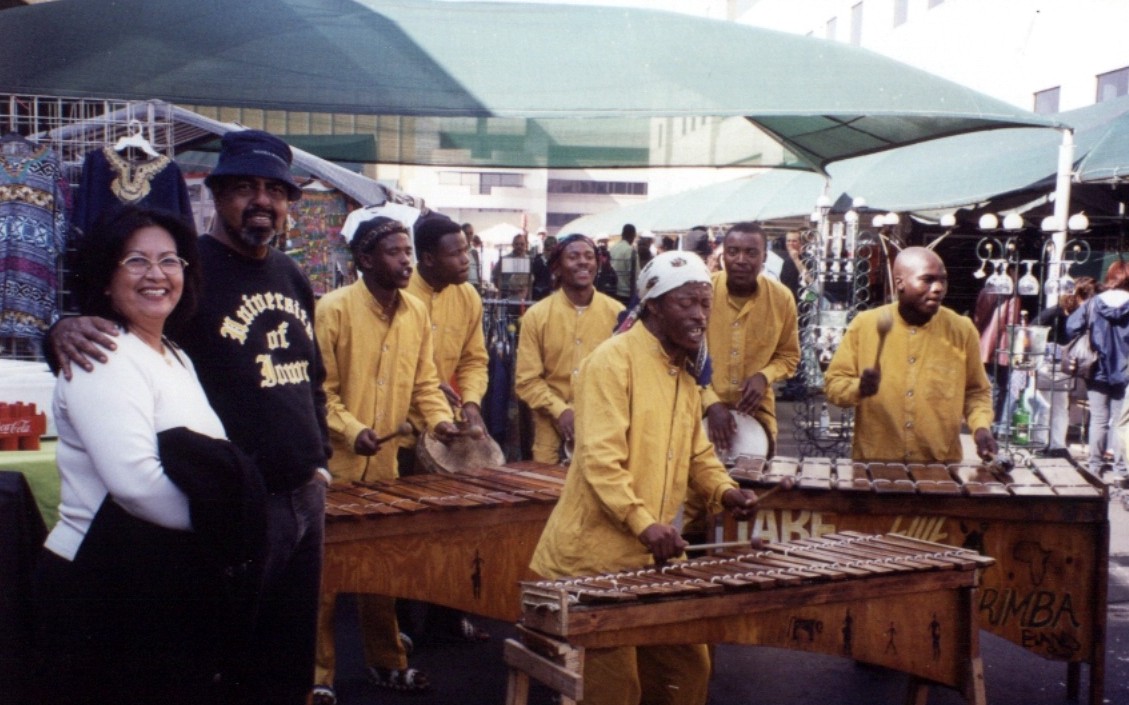

diversify educational exposure for Malaysians in all fields, the government began sending students to study in countries such as the United States, Japan, Korea, Germany, and India. Selected music educators in the government service were offered scholarships to study music education at the post-secondary level in the United States. Several of music educators in Malaysia have earned

masters degrees from American universities noted for quality music education programs

like Northwestern University, Indiana University and the University of Iowa.

Earlier, all significant music educators in Malaysia had been trained in England in a

performance-oriented system of music study at music conservatories. These Malaysians

were rigorously trained for a period of about four years to sing or to play a classical instrument to required proficiency levels. This musical training was coupled with the usual ensemble requirements, ear training and sight singing plus Western music theory, and European music history. Diploma-level degrees in music were then earned from prestigious music schools like the Royal College of Music, the Trinity College of Music, or the Birmingham School of Music.

The focus of this system of musical education was, of course, on exacting standards of performance. Pedagogical concerns in music education like curriculum development, teaching methods and strategies, music psychology, evaluation procedures, and foundations of music education appear to have received little or no focus. Also, music appreciation courses covering ethnic music and the music of non-European musical cultures were excluded, as were research procedures in music study. Some of these teachers went on to acquire music-teaching certificates, which were primarily geared toward individualized teaching of European art music and not for teaching general music in schools.

The aforesaid, however, in no way means that such pedagogically oriented subjects were not available for study at British universities. It is simply that, among Malaysians studying music in Britain, the main focus leaned towards performance rather than other areas.

Music Education in Colonial Times

Malaysia attained independence on August 31, 1957, after having been under varying degrees of colonial dominion, influence, or rule by several European maritime powers since 1511: Portugal, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Japan. The British first established formal public schools in Malaya during the early part of the nineteenth century. The English language was the medium of instruction in these public schools. The chief function of education during the British era, as mentioned earlier, was to equip the Malayan civil service with English-speaking locals primarily to serve British political and economic interests.

The Penang Free School, established by the British in 1816, was the first public

school in Malaya. Musical activities, if any, "in these early English schools were on a very modest scale and in the form of singing English folk and/or light classical songs, usually outside the formal curriculum. Any such activity very often depended on whether any member of the staff played the piano or had any other formal musical background.'? These musical activities were then presented at some auspicious school event such as the Speech Day, the Annual Sports Day, or at an official visit of a dignitary.

This utilitarian tradition of music remains strong in almost all educational institutions and official ceremonies. Music was seldom taught for its own sake. If any musical activity were conducted in the classroom, it was often part of the language program in the earlier grades; children sang standard nursery rhymes and folk songs in the English language. It was not uncommon to include some accompanying movement or fingerplay activities in efforts to dramatize the lyrical content of the songs. Educators felt that these musical activities helped the children to acquire a better "feel" of the English language and reduced the degree of stress and unfamiliarity usually associated with the process of learning a new or foreign language. Many of the larger urban schools included some additional measure of music in extracurricular activities such as marching bands, recorder ensembles, and choirs using British musical literature.

When the Japanese occupied Malaya (1941-1945), they promoted the singing of folk songs as a method of assisting students to learn the Japanese language, but this occupation left no observable impact on Malaysian music education.

Music education in Malaya after World War II improved to a degree. At school assemblies, children sang the school song, the respective state anthems, and "God Save The Queen." Musical activities were still mostly vocal with the modest addition of children's percussion instruments. Children also listened to school broadcasts of music lessons over the radio station, Radio Malaya.

During this time, the larger and better equipped English schools often organized

choirs and marching bands that helped to distinguish them as "exceptional." Military

band personnel, mostly retired, instructed and drilled the British-style marching bands in such schools. This is still a prevalent practice, as Malaysian music educators are not yet trained in marching-band techniques. Christian missionary schools in Malaysia also placed a strong emphasis on European-style choral singing and continue their strong traditions and leadership in this field.

Vernacular Schools

In addition to the prestigious British schools, three other types of primary schools

were also available during the colonial period: the Malay, Chinese, and Indian

(Tamil) schools. In each, the medium of instruction was the respective vernacular

tongue; consequently, they are called vernacular schools. About 58 percent of the

current Malaysian population of 17 million is 46 made up of the indigenous Malay races, with the Chinese and the Indians constituting the other two major "minority" groups.

The vernacular schools of colonial times were attended mostly by the children of the

lower socioeconomic classes, who usually sought employment after six years of primary

education. Very few were able to attend the urban English schools to continue their

education through the high school level, and the educational elitism almost always associated with the English schools by the local inhabitants caused many to believe that the vernacular schools were inferior.

Music education in the colonial vernacular schools was quite different from that in the British schools. In many Malay and Tamil schools, traditional and religious songs were sung, as were other songs containing moral-oriented lyrics. Monophonic singing was carried out in association with the language arts or religious programs, but there were few opportunities for public performance. Malay schools of colonial times had lessons in Qu'ranic recitation coupled with the singing of the nasyid (the generic Malay term for Islamic religious songs). Such activities, were never termed "music" nor thought of as such, because the term "music" usually evokes a secular association in the traditional Malay Muslim's mind. (In Malaysia, every Malay is also a Muslim, and thus the two words were often used synonymously.)

The late and noted ethnomusicologist Lois Ibsen al Faruqi has described Qu'ranic

recitation as cantillation combined with "improvised monophonic melody and

parlando rubato durational texture.'? In any case, sufficient musical elements exist in Qu'ranic recitation and nasyid for them to be considered musical activities. Thus, some forms of musical activity existed in Malay schools, but they were limited in nature and scope. As in the English schools, no "formal" music programs existed.

In the Chinese schools, there was much more vocal activity, coupled with a fair

measure of small-scale instrumental music making. Music reading was combined with

the Cheve system of musical notation that combines numbers and certain symbols.

Solfege singing was an integral part of music programs in Chinese schools. These two

trends probably paralleled developments in mainland China and Taiwan-at that time a

common practice of the Chinese community in Malaya. These Chinese schools placed

greater emphasis on singing (though not necessarily in the European bel canto style)

than most of the other vernacular schools.

The Chinese community was very supportive of these schools, both morally and financially, and such support allowed many of the Chinese schools to organize prestigious and costly choirs and marching bands. This tradition continues in many Chinese schools. Today, these vernacular schools exist at the primary level but have been very much homogenized and integrated under the purview of the Ministry of Education. Song books containing Chinese lyrics and the Cheve system of musical notation are readily available to the general public, thereby bearing continued testimony to the success of the sight singing music programs in the Chinese schools.

In the 70s, English was removed as the medium of instruction and the Malay language,

Bahasa Malaysia, which is also our national language, became the norm at

nearly all levels of Malaysian education. However, English is still taught as a compulsory second language in all educational institutions, and Malaysians who are conversant in the English language are looked up to and are much sought after for employment in many fields, particularly in the private sector.

Private Music Instruction

Personal instruction at the piano and other European musical instruments has been

available outside the public schools since the beginning of this century. In the early 1900s, musicians from India and the Philippines who were trained in Western musical notation and theory were brought to Malaysia to boost the manpower needed for military styled marching bands that were being formed in Malaya by the British." These bands were used in the ceremonial functions for which the British are very well known. It is believed that these imported musicians, particularly those from Goa, initiated the tradition of providing private and individualized instruction in European classical music.

Today, the piano has become the most popular classical instrument in Malaysia. A

1983 estimate by piano teachers "puts the figure of between 5,000 and 10,000 students

who sit for the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM,London) external examinations for the piano each year."? Probably as many or more sit for music theory examinations which are conducted, supervised, and evaluated by ABRSM personnel in Malaysia and England. The rudiments of western musical notation, theory, and song literature from about the time of Bach and Beethoven constitute the main content of the ABRSM syllabus, which is sequentially graded for children from grade I to grade 8; children usually study about eight years to achieve a grade 8 certificate. Some rudimentary ear training and sight reading is also done in this system. The highest qualification that may be acquired locally after grade 8 is the licentiate diploma from the ABRSM. The ABRSM qualifications, which are highly prized and respected in Malaysia, are acquired mostly through private study that is offered by literally thousands of ABRSM trained music teachers and hundreds of private music "schools" in the country. For many, particularly women, private music instruction is a lucrative vocation.

The ABRSM system has produced a share of positive influence in Malaysia. It has kept

some Malaysians continually acquainted with and highly appreciative of European classical music and increased the number of classical piano players in this country. A few have gone on to excel in music studies overseas and have "become successful classical musicians in Europe and the United States." The ABRSM influence has also brought about a significant negative influence. Because of the high costs involved, this system of music education has almost always excluded children from the rural population and most of those from the lower socioeconomic classes. It has also encouraged a conservative and narrow musical outlook, in that some ABRSM-trained Malaysians tend to view all music worth knowing as a homogeneous,monolithic, European structure.

The ABRSM influence has also brought about another significant negative result for

some Malaysian parents who aspire to the point of obsession to obtain ABRSM certificates for their children. This parental pressure, coupled with the rigorous training, competitive testing, and narrow scope of the ABRSM system of musical study, may have "turned off" many musically inclined and talented children. This much-undesired outcome can also be attributed to the fact that many key concepts in music education like creativity, improvisation, and other student-centered activities are considered unimportant in the present ABRSM system.

Many Malaysians do not seem to realize that the ABRSMapproach to music education

may not be totally suited to the contemporary Malaysian context, for the ABRSM

system essentially functions with rationales and objectives that are designed to perpetuate only European classical music traditions. Other music examinations with certification have also been conducted locally by private music schools, primarily for the organ and the guitar. Most of these local music schools and establishments are peripheral developments of highly successful marketing strategies employed by international corporations to boost the sale of musical instruments such

as pianos and electronic organs for the home. Although the motives of these schools may prove to be suspect, in all fairness they have demonstrated more interest in innovative teaching strategies and approaches than can be found in the ABRSM school of thought. The musical content in this system includes popular music and jazz and has therefore successfully attracted an appreciable number of students, including those from middle-class homes.

Curricular Content in Malaysian Schools Since 1983 Content and methods in education are closely tied to national aspirations, ideology, and philosophy. Music education was introduced as a regular subject in the primary schools' curriculum in 1983. The goals and objectives for music education at this embryonic stage are based on what the government, in consultation with Malaysian educators,deems beneficial for the people. The current Malaysian national philosophy for education aspires to produce citizens who are not only well-educated, united, patriotic, and progressive in their thinking, but who also possess good morals and a firm belief in the Almighty. Music education in Malaysian public schools has been patterned to support these and other ancillary goals. Through improved music education, it is anticipated that students will make wiser use of their leisure time and become better able to enjoy music both now and in the future. It is also expected that musical potential in

the young will be detected early, and that participation in musical activities will provide children with another healthy avenue for their creativity and enjoyment.

Music is also expected to enhance students' academic performance in other subjects through the inclusion of some interdisciplinary material in the music program. Thus music serves a utilitarian purpose in Malaysian education. The main vehicle for the delivery of formal music education in Malaysian public schools continues to be the vocal medium. "Rote before note" is the rule rather than the exception through grade Some effort is made to acquaint children with musical notation from grades 4 through 6, but this has met with only minimal success. Sometimes students play the recorder and percussion instruments. Performance opportunities arise mainly through annual inter-school competitions at the district and state levels or during an important school event. Student achievement in music is evaluated with cognitive tests and other cumulative assessments throughout the six years of primary education, but these scores are not taken into consideration when the student's overall academic progress is determined.

At the secondary level, music education is not compulsory but is offered as an elective at two of the national-level examinations which all Malaysians take in the ninth and eleventh years of schooling. The syllabi for these examinations are patterned along the lines of the ABRSM content, with some traces

of Malaysian traditional music added on to the music appreciation areas. The syllabi for these examinations are centrally regulated and prepared by the Ministry of Education.

Basic Music Teacher Education

From 1957, when Malaysia attained independence from the British, music was introduced in teacher training institutions as a self-enrichment program. All student teachers were required to sing and play the recorder as well as to learn the rudiments of traditional Western music theory. Beginning in the early 1960s, student teachers were trained to teach music at the Maktab Perguruan Lembah Pantai (Lembah Pantai Teachers' College) in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur, although music was still not included in the formal curriculum of public schools. The content of this new course was a slightly modified form of the self-enrichment program first introduced in teacher training institutions in 1957. In addition to basic singing, recorder, and theory, there was also some choral work included. During this period, an Englishman, Harold Ashcroft, was quite prominent in Malaysian music education. Many of Ashcroft's students speak of the passion and love that he had for music-European classical music -and the rigorous work that he required of them.

The leaders in music education throughout the 1970s, however, were all Malaysians

trained in Britain or in the ABRSM school of thought. The key figures were Khoo Soon

Teong, Basil ]ayatilaka, Ranji Knight, and Nazri Ahmad. They were centrally involved

in planning the curricular content for music education programs in the public schools

and teacher training colleges through the 70s,and may be credited for the earliest attempts to include Malaysian music, such as patriotic and traditional songs, as part of the repertoire taught in the schools.

In 1970, the role of providing basic teacher training for music teachers was taken over by the Maktab Perguruan Ilmu Khas in Kuala Lumpur. The curricular content for the basic music teacher education program remained static until 1980, when guitar study became compulsory for all student music teachers. Nazri Ahmad, who headed the Music Department of the Maktab Perguruan Hum Khas between 1979 and 1987, was largely responsible for this innovation. He had graduated from the Royal College of Music in London in the early 70s and then studied music education at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, where he earned his M.A. in 1977. Thus, he also became the first Malaysian music educator to study music education in the United States.

Major curricular changes in teacher education were made in 1988, when keyboard

skills, music appreciation, music pedagogy,and music history were added to the existing areas in the teacher-training program in the colleges. This writer sat on the Ministry's committee to revise the music syllabus for teacher-education colleges in February 1988. There was some disagreement about the changes, particularly from music lecturers trained in the ABRSM system, and another committee continued work on the syllabus in May 1989. The final syllabus is a version of the original syllabus of February 1988, in which the new areas are retained, as there seemed no convincing reason to remove them. It appears that the new areas are here to stay, and the curricular innovations made in February 1988 will result in a major shift away from the traditional ABRSM-based approach to music education in Malaysia.

In Malaysia there are many teachers who may be considered pioneers in the teaching

of music as a formal subject in the schools Some had taken music only as an elective

subject in their basic teacher-training programs,and others were regular classroom

teachers who could playa musical instrument and were consequently looked upon as

music educators by their school principals and required to teach music in the schools. Together, these teachers played an important role in efforts to establish music in the public school curriculum.

The rapid increase of the school population is challenging these teachers, as well as

the teacher training institutions, to keep up with students' needs for music education. The school population has more than quadrupled since independence, from

870,362 in 1956 to 3,414,175 in the mid 1980s. The enrollment of music students

into teacher training colleges has steadily increased also: In 1980, there were fewer

than 80 music students enrolled in basic teacher training. Today, there are about 550. This increase has primarily been a consequence of music entering the formal primary school curriculum in 1983.

Specialized Music Teacher Education

A major development in the history of Malaysian teacher education was the establishment of the Maktab Perguruan Ilmu Khas in Kuala Lumpur in 1959. This college was established to train specialized teachers in various areas such as physical education, art education, and special education (counseling,remedial, teaching the handicapped). A one-year music education course for certified teachers who have had at least five years general teaching experience was added to the program in 1971; teachers must have an ABRSM qualification or other proven musical skill to be eligible. Since 1983, another teacher college, the Maktab Perguruan Perseketuan in Pulau Pinang, has also been involved in the task of training both basic

and specialist music teachers.

The syllabus for this one-year music education course, first designed in 1970,

includes singing, music theory, recorder, children's percussion ensemble, scoring,

composition, and music appreciation. In 1980, the guitar was introduced as a compulsory instrument for all specialist music teacher-trainees. An average of 20 specialist music teachers are trained annually at the Maktab Perguran Ilmu Khas. Most of the graduates have served as itinerant music teachers in schools, music lecturers in teacher-training institutions, and as music administrators in state education departments. Thus, the college has become known as a leader in Malaysian

music education.

Music in the Formal Curriculum

The growing size of the Malaysian middle class and the general well-being of the

people in the 1970s signaled the establishment of music as a regular subject in the

school curriculum. In 1972, music was introduced as an elective subject for the

Lower Certificate of Education and the Malaysian Certificate of Education examinations, which are important public examinations taken by all Malaysian children in the ninth and eleventh years of their schooling.

In the early 1970s, many educators and parents spoke out against the old curriculum,

which was criticized as being too rigid, too academic, and too examination-oriented.

After some difficult planning and a number of recommendations from the Cabinet

Committee on Education, the New Primary Schools Curriculum was tested in various

Malaysian schools in 1982 and implemented throughout the country in 1983.

Of note, the new curriculum included music as a compulsory subject at the primary

school level for the first time. The inclusion of music as a regular subject in the New Primary School Curriculum may be viewed as a crucial milestone in the history of Malaysian music education as every school-age Malaysian child, irrespective of socioeconomic background, now has the opportunity to learn music as a matter of right rather than of privilege.

Teaching Methods

Because of a dire shortage of music teachers, many general classroom teachers

have been required to teach music since 1983. The content for music classes is

provided to teachers in the form of sequential lessons recorded on cassette tapes with accompanying text books and work sheets; all are prepared, distributed, and regulated by the Ministry of Education. While this practice helps classroom teachers who are untrained in music, those teachers who are capable of teaching music find very little opportunity to digress from these centrally regulated materials.

Thus a significant number of classroom teachers have seldom done more in music

classes than switch on and turn off the cassette player. This is an unfortunate result of an enthusiastic effort to get music into the curriculum, coupled with inattention to the lack of trained music teachers. To attempt to ensure the success of the new music classes, many general classroom teachers attended music courses lasting from three to four weeks each over a period of three years at

teacher training colleges throughout the country. About 5,000 such music teachers

were trained between 1982 and 1984 and given attendance certificates which brought

them very little financial reward or academic recognition. Some of these teachers recognized that they had neither musical aptitude nor the inclination to teach music but were merely following directives of their superiors.

Today, many of these teachers still use the pedagogical strategies they learned in these courses, for there has been no significant effort to provide more complete courses for them. The musical material first provided by the Ministry in 1983 has not been revised or updated. Essentially, music teachers in Malaysia are

trained to teach singing with solfege and notation. A typical lesson begins with

breathing exercises and solfege singing. The two methods often used to teach a song are the "patterning" method and the "whole" method. In the former, used in the lower

grades, the teacher models a phrase of the song repeatedly. Children echo along until

the phrase is satisfactorily learned and then move on to the next phrase. This process continues until the entire song is learned. In the whole method, the teacher sings (or plays the piano) through the whole song again and again while the children sing along with increasing familiarity (and volume) until the song is deemed satisfactorily sung. When the teacher determines that the children have learned the melodic line, the action literally begins. Teachers are taught how to make use of action songs (like "Skip to my Lou"), fingerplay songs (like "Eency Weency Spider"), and simple rounds and canons. Actions and games also dramatize the lyrical content of songs. Clapping the rhythm of the song is a popular interpretation of "action," and walking, running, skipping, or playing games to music are also highly recommended and encouraged. Other songs contain texts designed to teach children good morals and personal hygiene, stressing societal norms and values, and a sense of patriotism.

Much of the classroom teaching, however, barely skims the cognitive aspects of musical learning. This is glaringly apparent in Malaysian teaching methods, and the main reason lies in the fact that musical literacy is not among the stated goals or objectives. Because foreign-trained music educators are working to emphasize it, however, it should not be long before musical literacy becomes accepted as a major goal. Only since 1988 have student music teachers been exposed to major approaches

to music education like Kodaly and Orff. They are also being given more exposure to

pedagogical approaches that emphasize student-centered activities.

Conclusions

The government and top educational administrators have always shown positive

attitudes towards criticism and change, especially if such criticism came from music

educators with tertiary qualifications. However, such criticism has had to be made

through the proper channels of governmental bureaucracy, and sometimes valid ideas and suggestions are "shot down" by middle-ranking supervisors who disagree with innovative suggestions. An ad hoc committee spearheaded by mostly American-trained' music educators, is now working on the constitution of the yet-to-be registered Malaysian Music Educators Association (MMEA).The MMEA aspires to address many professional problems in the arena of music education as well as acting as a

"watchdog" for the music education profession in the country.

Another interesting development in Malaysian music education is the fact that an

increasing number of people are beginning to see the importance of our own folk and

traditional musics." The vast array of Malaysian traditional music extant today,

including the folk and traditional musics of the migrant races, certainly bears ample

testimony to the fact that the folk and traditional musics of all Malaysians were very much kept alive throughout the years of colonial dominion in Malaysia. The government's "Visit Malaysia Year 1990" campaign also indirectly revived local interest in Malaysian traditional music and other traditions.

Almost daily, traditional music and other cultural fare are presented in Kuala Lumpur and elsewhere, albeit for the benefit of tourists. Efforts are now underway to include the study of Malaysian traditional music in the formal music curriculum for all primary schools. It might well be that the many developments that have occurred in the music education scene in recent years augur well

for the future of music education in Malaysia. The tide is certainly changing. However, it appears that solutions to problems pertaining to rationale and pedagogy for music education would, initially and to a great degree, rest primarily on the leadership of foreign trained music educators and in their ability to

interpret realistically and pragmatically Western ideas from a Malaysian perspective.

To succeed, these efforts should respect the financial constraints, expectations, and

societal values of Malaysians.

Many challenges are in store for the entire music education community in Malaysia in

the years ahead. A major concern is to get music education into all levels of Malaysian education, including the tertiary levels. There may be no drastic change in the national educational philosophy, but most certainly innovations in teaching strategies, objectives, evaluation procedures, approaches and curricular content can be expected in the near future.

Acknowledgements:

The author wishes to thank his many colleagues and friends who have patiently read through this article. In particular, I thank my immediate superior, Ms. Nik Faizah Mustapha, the principal of the Maktab Perguruan Ilmu Khas, who also read the final draft of this article and offered some very useful suggestions. All their most valued comments, suggestions, and encouragements have made this modest effort possible. ~

No comments:

Post a Comment